本文延续了有关 Open AI 智能中英文写作话题,从中节选了美国作者 Rebecca Monteleon 的有关作品。

Writing text that can be understood by as many people as possible seems like an obvious best practice. But from news media to legal guidance to academic research, the way we write often creates barriers to who can read it. Plain language—a style of writing that uses simplified sentences, everyday vocabulary, and clear structure—aims to remove those barriers.

Writing text that can be understood by as many people as possible seems like an obvious best practice. But from news media to legal guidance to academic research, the way we write often creates barriers to who can read it. Plain language—a style of writing that uses simplified sentences, everyday vocabulary, and clear structure—aims to remove those barriers.

Good writing is Easy to read. But a lot of writing is hard to read. Some people can’t read hard writing. Plain language fixes this problem. It makes writing easy to read for more people.

Plain language is useful for everyone, but especially for those who are often denied the opportunity to engage with and comment on public writing. This includes the 20% of the population with learning disabilities, a number of the more than 7 million people in the US with intellectual disabilities (ID), readers for whom English is not a first language and people with limited access to education, among others.

Plain language is helpful for everyone. But it is really good for people who may find other kinds of writing hard to read. That includes:

- People with learning disabilities.

- People with intellectual disabilities (ID).

- People who are learning to speak English.

- People who did not go to school or went to school less than they wanted to.

These audiences are routinely excluded from public dialogues, including dialogues about themselves. People with disabilities are also often excluded from writing or sharing their own stories first-hand due to lower vocabulary skills, learning differences, and intellectual disabilities. For example, throughout much of US history, people with ID have had decisions made on their behalf based on the presumption that they do not and cannot understand. This, on top of discriminatory attitudes and stigma, has led to infantilization, institutionalization and eugenic sterilization.

These groups of people get left out of the conversation a lot. Even when the conversation is about them.

For example, many people think people with ID don’t understand how to make choices for themselves. Nondisabled people make choices for them. These choices sometimes hurt people with ID. Throughout history, many people with ID have been:

- Treated like children.

- Forced to live in institutions, group homes, and nursing homes.

- Forced to have surgery so they could not have children.

Additionally, there is a tendency to censor content for these audiences rather than explain it, which can contribute to continued disparities, like the higher rate at which people with ID experience sexual violence than non-disabled people.

Writers will censor writing for these groups. To censor something means to take out information the writer thinks is not appropriate. Taking out information can make some problems worse.

For example, people with ID experience sexual violence more than non-disabled people. But some writers think people with ID should not read about sex or sexual violence. So, readers don’t have all the information they need.

The benefits of plain language aren’t limited to universally challenging texts like legal documents and tax forms. Even everyday writing, like news articles, can still pose a barrier for some readers.

Some kinds of writing are hard for everyone to read, like tax forms. But everyday writing, like the news, can be hard to read too.

How does a human assess readability?Let’s walk through how Rebecca, an expert in plain language, translates a text to be more readable. We'll use an excerpt from her translation of a ProPublica article by Amy Silverman in the following example.

Here is an example for how to make writing easier to read. Rebecca wrote this example. She is an expert in plain language. This quote is from a news article. Amy Silverman wrote it for ProPublica. Rebecca wrote it in plain language.

An example of translating text from standard to plain language where you can select Rebecca's comments to learn more about her translation process.

Plain language translating: side-by-side comparisonORIGINAL

Kyra is autistic and profoundly deaf. She was born prematurely at about 27 weeks, just a little over 2 pounds, which has impacted pretty much everything: eyesight, hearing, digestion, sleep patterns. A strong tremor in her hand makes it impossible for her to use American Sign Language. Her parents think she recognizes a couple of dozen signs.

PLAIN LANGUAGE

Kyra is autistic and deaf. She was born early. She was very small when she was born. She has trouble seeing, hearing, eating and sleeping. Her hand shakes so she does not do sign language. Her parents think she knows some signs.

More about Rebecca’s translation process

When doing a plain language translation, my first step is always to do a close read of the original text. I identify the main points, the order information is presented, and any terms or concepts that I think will need to be defined or replaced. I always think to myself “what does this sentence/idea/concept assume the reader already knows?” There is so much implied in how we write, and plain language should aim to make the implicit more explicit.

My first step is to read the whole paragraph. I look for:

- The main points.

- The order things are written in.

- Any words or ideas that I will need to explain.

A lot of writing assumes the reader already knows something about the topic. Plain language should not assume that. I will explain things fully.

Once I start translating, I typically take a paragraph-by-paragraph approach rather than sentence-by-sentence, because often I will need to re-order information, add definitions or examples, or reintroduce characters and ideas at the top of a new paragraph. Focusing too much on the sentence-level translation can mean losing sight of the bigger picture.

When I write something in plain language, I don’t take every sentence from the original writing. I look at the big ideas. I:

- Put things in a different order.

- Add definitions and examples.

- Remind the reader about key characters and ideas.

As more people have recognized the practical value of plain language, researchers have sought to quantify the “plainness” of writing through readability formulas—mathematical models that assign numerical scores to text, indicating how understandable they are.

Researchers try to measure how easy something is to read. They use math to give the writing a score. The score tells us how easy something is to read. These are called “readability scores.”

Though most readability formulas were designed to offer rough difficulty estimates for specific groups of readers, their usage varies greatly, with the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality warning that “these formulas are often interpreted and used in ways that go well beyond what they measure.”

Readability scores just give us an “estimate” about how hard something is to read. That means the scores are not perfect. But they give us a good idea about how hard it might be for different groups of people to read something.

But the Agency for Healthcare Research and Quality said, “these formulas are often interpreted and used in ways that go well beyond what they measure.” This quote means people use these scores in ways they were not made to be used.

Moreover, the simplicity of readability checkers has enabled their widespread adoption. Military engineers use them to help write technical documents. Governments and doctors use them to guide communication for a general audience. Schools and textbook manufacturers use them to tailor reading assignments to particular grade levels and students.

Readability scores are easy to understand. Many people use these scores to help them write. Some groups that use readability scores are:

- The military.

- The government.

- Doctors.

- Schools.

To better understand how readability scores work—and how they can fail—let’s look at three representative examples.

Let’s look at three examples of readability scores. They can help us understand how these scores work and how they can fail.

Algorithm #1: Syllable CountThe Flesch-Kincaid Grade level formula looks, in part, at syllable count, based on the idea that words with fewer syllables are easier to understand.

The Flesch-Kincaid formula measures two things:

- How long words are.

- How many words are in a sentence.

The formula says the shorter the words and sentence, the easier it is to read.

An interactive showing what the Flesch-Kincaid algorithm considers a easy, medium, and hard sentence. The algorithm deems sentences with lower syllable counts to be easier, so when long multisyllabic words are added (even if they are easy words), the algorithm says it's a hard sentence. If we add short but obscure words, the algorithm thinks it's an easier sentence. We see that the Flesch-Kincaid algorithm isn't able to handle much complexity when it comes to assessing readability.

What happens if we only care about syllablesChange reading level

Easy

Medium

Hard

The below text is at a 2.34 (2nd grade) grade reading level according to Flesch-Kincaid

The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog.

The dun fox cleared that slouch of a dog at full tilt.

The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog.

The wonderful, beautiful fox jumped over the unbelievably lazy dog.

The two factors considered by Flesch–Kincaid are number of words per sentence and number of syllables per word. This is a short sentence with only two multi-syllable words (“over” and “lazy”), so the Flesch–Kincaid formula assigns it a low grade level.

Algorithm #2: Difficult wordsThe Dale-Chall Readability Formula considers the proportion of difficult words, where it deems a word “difficult” if it is not on a list of 3,000 words familiar to fourth-grade students.

The Dale-Chall Readability Formula considers the proportion of difficult words, where it deems a word “difficult” if it is not on a list of 3,000 words familiar to fourth-grade students.

Dale-Chall is another readability score. It measures two things:

- How long each sentence is.

- The number of easy or hard words.

Dale-Chall uses a list of 3,000 easy words. Dale-Chall says these are words most 4th graders know. Any other word is a hard word.

One risk in the use of vocabulary lists is that the vocabulary of the readers surveyed to create them may not match the vocabulary of the intended audience. The original Dale-Chall list of “familiar words” was compiled in 1948 through a survey of U.S. fourth-graders, and even the most recent update to the list in 1995 retains obsolete words like “Negro” and “homely” while omitting “computer.”

But not everyone knows the same words. Dale-Chall made the first easy word list in 1948. They updated the list in 1995.

We don’t use the same words now that we did back then. The list has words most people don’t use now, like “Negro” and “homely.” And it doesn’t have words a lot of people use now, like “computer.”

An interactive showing what the Dale-Chall algorithm considers a easy, medium, and hard sentence. Dale-Chall considers average sentence length along with how many difficult words are used, where “difficult” words are words that don't appear on the Dale-Chall list. If we add words that are unfamiliar (like dinosaur or dude) the algorithm says it's a difficult sentence. If we simply add a sentence that just contains the exclamation "Yes!", that lowers the average sentence length and makes the algorithm say it's an easier sentence. We see that the Dale-Chall algorithm isn't able to handle much complexity when it comes to assessing readability.

What happens if we only care about“difficult” wordsChange reading level

Easy

Medium

Hard

The below text is at a 0.45 (4th grade or below) grade reading level according to Dale-Chall

The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog.

Yes! The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog.

The quick brown fox jumped over the lazy dog.

Dale–Chall considers average sentence length along with percentage of difficult words (PDW), where “difficult” words are words that don't appear on the Dale–Chall list. This is a short sentence made entirely of words on the Dale–Chall list, so its ASL score is low and its PDW score is zero, yielding a score of 0.45. Since the formula was calibrated on a group of 4th grade students, all scores below 5.0 are collapsed into a single readability category representing “4th grade and below.”

Algorithm #3: Algorithmic black boxesMore recently, US schools and textbook manufacturers have standardized their curricula on the Lexile Framework for Reading, a set of readability algorithms and vocabulary lists designed to automatically match students with appropriately difficult books. Publishers apply Lexile to their texts to rate their difficulty. A Lexile score of 210 indicates an easy-to-read book, while a score of 1730 indicates a very challenging one. A reading comprehension test assigns a corresponding reading score to each student, after which teachers pair students with texts that have comparable Lexile scores.

Lexile Framework for Reading is another formula to measure how easy something is to read. Schools and textbook writers use Lexile. Lexile helps match students with books they are able to read.

Here is how it works:

- Lexile scores books. It rates them as easy or hard to read.

- Students take a reading test. It tells them how well they read.

- Teachers give students books that won’t be too easy or too hard for them to read.

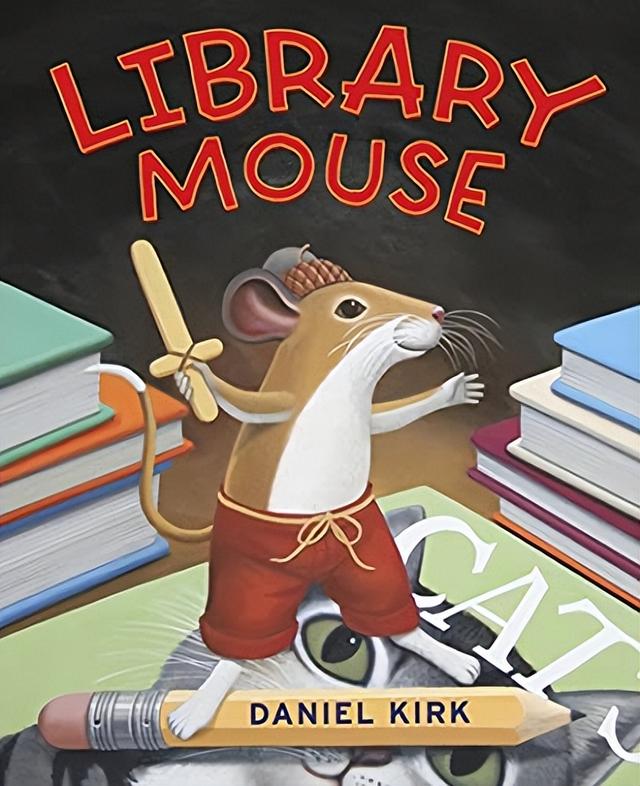

The approach sounds simple enough, but critics have pointed out absurdities in Lexile's results. According to Lexile, The Grapes of Wrath (Lexile score: 680) is easier to understand than the Nancy Drew mystery Nancy's Mysterious Letter (score: 720), but neither of these is as challenging as The Library Mouse (score: 860), a 32-page illustrated children's book.

But the scores Lexile gives books don’t always make sense. Here’s an example. Lexile says:

- Lexile says that The Grapes of Wrath is a pretty easy book to read. The Grapes of Wrath is a book for adults. It is over 400 pages long and has many complex themes and ideas.

- Lexile says the Nancy Drew book Nancy’s Mysterious Letter is harder to read than The Grapes of Wrath. Nancy Drew books are made for preteens. Most people would consider it much easier to read than The Grapes of Wrath.

- Lexile says The Library Mouse is harder to read than the Nancy Drew book or The Grapes of Wrath. The Library Mouse is a picture book for children.

It does not make sense that a children’s picture book would be harder to read than a book for adults.

Images of three book covers arranged by how difficult the Lexile algorithm thinks they are. It says Grapes of Wrath is the easiest, followed by Nancy's Mysterious Letter, and the hardest is The Library Mouse, a 32-page illustrated children's book. This doesn't make much sense, most people would say that Grapes of Wrath is much more difficult than a simple children's book.How Lexile scores popular books for children

680(5th grade)

720(7th grade)

860(10th grade)

How exactly are Lexile scores calculated? Unfortunately for us, the Lexile Framework is the intellectual property of MetaMetrics, the private company that created it, so we can only guess at the secret recipe, but it's a pretty good bet that Lexile scores depend on a mixture of the same factors used in Flesch–Kincaid and other open-source readability measures.

We don’t know how Lexile decides how hard each book is. MetaMetrics is the company that made Lexile. They do not share what math they do to get their readability scores. But it is probably close to the other formulas we looked at. We know Lexile looks at:

- How long words are.

- How long each sentence is.

- How familiar the words are.

- If things are repeated.

Formulas based on surface level text properties and word frequency have clear limitations. None of them consider how well organized the information is, or whether the sentences and paragraphs are coherent. None consider the role of grammatical tense. None account for the explanation of acronyms and jargon. None would balk at Jack Torrance's rambling and meaningless draft in The Shining, endlessly repeating “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy.”

None of these formulas are perfect. They don’t measure:

- The order of the sentences.

- If the writing makes sense.

- Grammar.

- If the writer explains hard words and phrases.

These formulas would have no problem with the scene in The Shining where Jack Torrance writes “All work and no play makes Jack a dull boy,” over and over again. They do not check if the writing means anything.

But proprietary tech like Lexile has some of the most disconcerting aspects of both worlds. As flawed as Flesch-Kincaid or Dale-Chall, but opaque and unexplainable. The main benefit of the F-K and D-C formulas (and other simple algorithms like Gunning-Fog and SMOG) is their transparency. A broken system locked in a black box can't even offer this.

At least we know how Flesch-Kincaid and Dale-Chall work. They are not perfect but we can explain them. We don’t even know what Lexile measures.

Where Do We Go From Here?In recent decades, as disability activists have won more civil rights, both in the US and internationally, accessible writing has gained greater attention. And with this attention comes the very real possibility that plain language will be outsourced to blackbox technologies that are grounded in antiquated data.

People with disabilities have more rights than ever before. More people are thinking about how to write for all kinds of readers. And so more people may try to use formulas like Flesch-Kincaid or Dale-Chall. But these formulas have problems.

Technology alone isn’t the answer. Even the most thoughtful algorithms and robust data sets lack context. Ultimately, the effectiveness of plain language translations comes down to engagement with your audience. Engagement that doesn’t make assumptions about what the audience understands, but will instead ask them to find out. Engagement that’s willing to work directly with people with disabilities or limited access to education, and not through intermediaries. As disabled advocates and organizations led by disabled people have been saying all along: “Nothing about us without us.”

,