Causes

起因

On the surface, the most apparent cause of the Enlightenment was the Thirty Years’ War. This horribly destructive war, which lasted from 1618 to 1648, compelled German writers to pen harsh criticisms regarding the ideas of nationalism and warfare. These authors, such as Hugo Grotius and John Comenius, were some of the first Enlightenment minds to go against tradition and propose better solutions. At the same time, European thinkers’ interest in the tangible world developed into Scientific Study, while greater Exploration of the world exposed Europe to other cultures and philosophies. Finally, centuries of mistreatment at the hands of monarchies and the church brought average citizens in Europe to a breaking point, and the most intelligent and vocal finally decided to speak out.

从表面上看,启蒙运动最明显的原因是三十年战争。这场从1618年持续到1648年的毁灭性战争,迫使德国作家对民族主义和战争的思想进行了严厉的批评。这些作家,如雨果·格老秀斯和约翰·科米纽斯,都是启蒙运动的先驱,他们反对传统,提出更好的解决方案。与此同时,欧洲思想家对有形世界的兴趣发展成为科学研究,而对世界的更大探索使欧洲接触到其他文化和哲学。最后,几个世纪以来,君主和教会对平民的虐待把欧洲的普通民众逼到了崩溃的边缘,最智慧的、最有发言权的人终于决定大声疾呼。

Pre-Enlightenment Discoveries

启蒙前的发现

The Enlightenment developed through a snowball effect: small advances triggered larger ones, and before Europe and the world knew it, almost two centuries of philosophizing and innovation had ensued. These studies generally began in the fields of earth science and astronomy, as notables such as Johannes Kepler and Galileo Galilei took the old, beloved “truths” of Aristotle and disproved them. Thinkers such as René Descartes and Francis Bacon revised the scientific method, setting the stage for Isaac Newton and his landmark discoveries in physics. From these discoveries emerged a system for observing the world and making testable Hypotheses based on those observations. At the same time, however, scientists faced ever-increasing scorn and skepticism from people in the religious community, who felt threatened by science and its attempts to explain matters of faith. Nevertheless, the progressive, rebellious spirit of these scientists would inspire a century’s worth of thinkers.

启蒙运动是通过滚雪球效应发展起来的:小的进步引发大的进步,在欧洲和世界意识到这一点之前,几乎两个世纪的哲学思考和创新已经接踵而至。这些研究通常始于地球科学和天文学领域,因为约翰内斯·开普勒(Johannes Kepler)和伽利略(Galileo galileititon)等知名人士对亚里士多德(Aristotle)古老而受人喜爱的“真理”进行了驳斥。笛卡尔(Rene Descartes)和培根(Francis Bacon)等思想家修正了科学方法,为艾萨克·牛顿(Isaac Newton)及其在物理学上的里程碑式发现奠定了基础。从这些发现中出现了一个观察世界的系统,并根据这些观察做出可验证的假设。然而,与此同时,科学家们面临着来自宗教团体的越来越多的蔑视和怀疑,他们感到科学及其解释信仰问题的努力对他们构成了威胁。然而,这些科学家的进步和反叛精神将激发一个世纪的思想家的价值。

The Enlightenment in England

英国的启蒙运动

The first major Enlightenment figure in England was Thomas Hobbes, who caused great controversy with the release of his provocative treatise Leviathan (1651). Taking a sociological perspective, Hobbes felt that by nature, people were self-serving and preoccupied with the gathering of a limited number of resources. To keep balance, Hobbes continued, it was essential to have a single intimidating ruler. A half century later, John Locke came into the picture, promoting the opposite type of government—a representative government—in his Two Treatises of Government (1690). Although Hobbes would be more influential among his contemporaries, it was clear that Locke’s message was closer to the English people’s hearts and minds. Just before the turn of the century, in 1688, English Protestants helped overthrow the Catholic king James Ii and installed the Protestant monarchs William And Mary. In the aftermath of this Glorious Revolution, the English government ratified a new Bill of Rights that granted more personal freedoms.

英国启蒙运动的第一个主要人物是托马斯·霍布斯,他在1651年出版了具有煽动性的著作《利维坦》,引起了巨大的争议。从社会学的角度来看,霍布斯认为,人的本性是自私的,专注于收集有限的资源。霍布斯继续说,为了保持平衡,必须有一个令人生畏的统治者。半个世纪后,约翰·洛克(John Locke)在他的《政府论》(1690)中提出了与之相反的政府类型——代议制政府。尽管霍布斯在他同时代的人当中会更有影响力,但洛克的观点显然更贴近英国人的内心和思想。就在世纪之交的1688年,英国新教徒帮助推翻了信奉天主教的国王詹姆斯二世(king James Ii),并建立了信奉新教的君主威廉(William)和玛丽(Mary)。在这场光荣革命之后,英国政府批准了一项赋予更多个人自由的新权利法案。

The Enlightenment in France

法国的启蒙运动

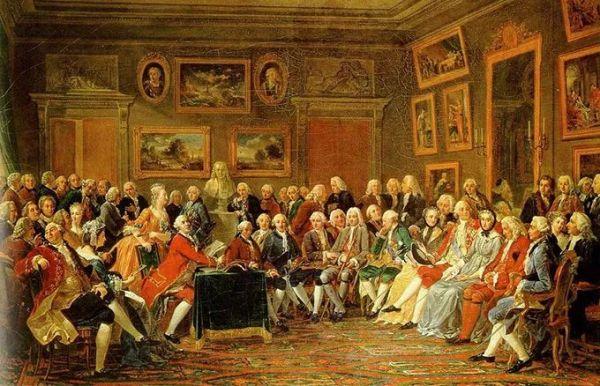

Many of the major French Enlightenment thinkers, or Philosophes, were born in the years after the Glorious Revolution, so France’s Enlightenment came a bit later, in the mid-1700s. The philosophes, though varying in style and area of particular concern, generally emphasized the power of reason and sought to discover the natural laws governing human society. The Baron De Montesquieu tackled politics by elaborating upon Locke's work, solidifying concepts such as the Separation Of Power by means of divisions in government. Voltaire took a more caustic approach, choosing to incite social and political change by means of satire and criticism. Although Voltaire’s satires arguably sparked little in the way of concrete change, Voltaire nevertheless was adept at exposing injustices and appealed to a wide range of readers. His short novel Candide is regarded as one of the seminal works in history. Denis Diderot, unlike Montesquieu and Voltaire, had no revolutionary aspirations; he was interested merely in collecting as much knowledge as possible for his mammoth Encyclopédie. The Encyclopédie, which ultimately weighed in at thirty-five volumes, would go on to spread Enlightenment knowledge to other countries around the world.

许多法国启蒙运动的主要思想家,或哲学家,都出生在光荣革命之后的年代,所以法国的启蒙运动来得晚一些,是在18世纪中期。哲学虽然在风格和特别关注的领域有所不同,但总体上强调理性的力量,并寻求发现支配人类社会的自然规律。孟德斯鸠男爵通过阐述洛克的著作来处理政治问题,他巩固了一些概念,比如通过政府内部的分开来实现权力分离。伏尔泰采取了一种更为严苛的方式,他选择通过讽刺和批评来煽动社会和政治变革。尽管伏尔泰的讽刺作品几乎没有引发什么实质性的变化,但伏尔泰却善于揭露不公,并吸引了广泛的读者。他的短篇小说《老实人》被认为是历史上影响深远的作品之一。与孟德斯鸠和伏尔泰不同,丹尼斯•狄德罗没有革命的抱负;他的兴趣仅仅是为他那本庞大的百科全书收集尽可能多的知识。这部百科全书最终有35卷,它将继续向世界其他国家传播启蒙知识。

Romanticism

浪漫主义

In reaction to the rather empirical philosophies of Voltaire and others, Jean-Jacques Rousseau wrote The Social Contract (1762), a work championing a form of government based on small, direct democracy that directly reflects the will of the population. Later, at the end of his career, he would write Confessions, a deeply personal reflection on his life. The unprecedented intimate perspective that Rousseau provided contributed to a burgeoning Romantic era that would be defined by an emphasis on emotion and instinct instead of reason.

作为对伏尔泰和其他人的经验主义哲学的回应,让-雅克•卢梭(Jean-Jacques Rousseau)撰写了《社会契约》(Social Contract, 1762),这部著作倡导一种建立在直接反映人民意愿的小型民主基础上的政府形式。后来,在他的职业生涯结束时,他写了《忏悔录》,对他的生活进行了深刻的个人反思。卢梭所提供的前所未有的亲密视角促成了一个迅速发展的浪漫主义时代,这个时代的定义是对情感和本能的情调,而不是理性。

Skepticism

怀疑论

Another undercurrent that threatened the prevailing principles of the Enlightenment was Skepticism. Skeptics questioned whether human society could really be perfected through the use of reason and denied the ability of rational thought to reveal universal truths. Their philosophies revolved around the idea that the perceived world is relative to the beholder and, as such, no one can be sure whether any truths actually exist.

Immanuel Kant, working in Germany during the late eighteenth century, took skepticism to its greatest lengths, arguing that man could truly know neither observed objects nor metaphysical concepts; rather, the experience of such things depends upon the psyche of the observer, thus rendering universal truths impossible. The theories of Kant, along with those of other skeptics such as David Hume, were influential enough to change the nature of European thought and effectively end the Enlightenment.

另一股威胁启蒙运动主流原则的暗流是怀疑主义。怀疑论者质疑人类社会是否真的可以通过使用理性来完善,并否认理性思维揭示普遍真理的能力。他们的哲学思想围绕着这样一种观点,即所感知的世界是相对于观察者而言的,因此,没有人能确定是否真的存在真理。18世纪晚期在德国工作的伊曼努尔•康德(Immanuel Kant)将怀疑论发挥到了极致,他认为,人既不可能真正知道观察到的物体,也不可能真正知道形而上学的概念;相反,这些事情的经验取决于观察者的心理,因此普遍的真理是不可能的。康德和大卫•休谟等其他怀疑论者的理论,对欧洲思想的本质产生了巨大的影响,并有效地终结了启蒙运动。

启蒙运动(法文:Siècle des Lumières,

英文:The Enlightenment,德文:die Aufklärung),指发生在17-18世纪的一场资产阶级和人民大众的反封建,反教会的思想文化运动。是继文艺复兴后的又一次反封建的思想解放运动。其核心思想是“理性崇拜”。这次运动有力批判了封建专制主义,宗教愚昧及特权主义,宣传了自由,民主和平等的思想。为欧洲资产阶级革命做了思想准备和舆论宣传。

这个时期的启蒙运动,覆盖了各个知识领域,如自然科学、哲学、伦理学、政治学、经济学、历史学、文学、教育学等等。启蒙运动同时为美国独立战争与法国大革命提供了框架,并且导致了资本主义和社会主义的兴起,与音乐史上的巴洛克时期以及艺术史上的新古典主义时期是同一时期。

“日行万步”的人,最终都怎样了?

“宜家效应”如何悄悄影响你的消费方式

拿破仑统治下的欧洲(1799-1815)

辉煌的历史 · 文艺复兴(1330年 - 1550年)

日本便利店有多便利?

三位奥运冠军告诉你为什么,挫折是最好的教育

超1亿人下载,霸榜121个国家!换脸应用FaceApp火爆全球

幸福就是, 唯美食与爱不能被辜负

【品读大师】查尔斯·狄更斯

挑战无塑料生活,不到一个月差点崩

■ 雅思提分月计划课程(在线小班)

■ 雅思写作批改服务(48小时内回复)

作者:雅思小伦哥来源:博珂英华(微信公众号)

博珂英华:专注财经以及英语的知识分享、教材编写和提升课程

,